This is an introduction to a number of short blogs on sources for researching Caribbean service personnel in the First World War.

At the outbreak of the First World War there were Caribbean and people of Caribbean descent already serving in the British army in British regiments and the West India Regiment, the Royal Navy and the merchant navy.

In the Caribbean the war was seen by many as a ‘white-man’s war’ or a European war and not their problem. But many wanted to serve to protect the Motherland and to fight as equals. Caribbeans living in Britain enlisted locally; people living in the Caribbean at first needed to travel to Britain to enlist. In Barbados and Trinidad the public arranged for citizens’ contingents to travel to the UK – these were ‘white’ middle-class men – planters, merchants, public servants and clerks, though correspondence with the Colonial Office suggests many were not pure-European. Many black men also made their way to Britain but the War Office resisted recruiting black Caribbeans and even suggesting repatriating some back to the Caribbean.

In the Caribbean there was a push to establish a Caribbean contingent comprising people from all colonies – for social and political reasons they did not want to join the West India Regiment – and to form their own regiment. After much resistance from the War Office the British West Indies Regiment was officially established on 26 October 1915.

There were three other Caribbean regiments who served abroad in the war: the West India Regiment, the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps (consisting of white men) and the Bermuda Militia Artillery (consisting of black men). I know that Bermuda is not in the Caribbean but historically it was considered by the British authorities as a West Indian colony.

Men also served in the Royal Navy and auxiliary services, the Royal Air Force (and predecessors Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service), and in the merchant navy – although not a military service was vital for the success of the war. Caribbeans also served in Canadian, and later in US forces. In addition, in the Caribbean men served in local defence forces, people supplied money, food and goods for the war effort, and many countries had prisoner of war camps.

However, while people hoped for equality there was racial discrimination in all services:

- the Bermuda regiments were segregated on racial grounds.

- black Caribbeans (from the Caribbean) were expected to join the West India Regiment or British West Indies Regiment rather than regular regiments.

- commissioned officers were to be ‘pure-European’ although it is clear from correspondence with the Colonial Office that many ‘white’ gentlemen may not have been pure-European. The Colonial Office frequently asked the War Office not to be so restrictive and to accept ‘slightly coloured’ gentlemen. By mid-1917 the War Office was granting temporary commissions to black men who had the support of their commanding officer and who could lead. Walter Tull, of Barbadian heritage was one such officer.

- soldiers in non-European colonial regiments were usually paid less and had less favourable pensions and allowance than other soldiers in British regiments – the argument was that the cost of living in the colonies was cheaper than in the UK – a similar argument put forward recently for paying the Gurkhas less than other soldiers in the British army. The West India Regiment was considered a ‘native’ regiment but British West Indies Regiment was treated as a regular regiment – until the end of the war when under Army Order no 1, 1918, they did not get a pay rise. Neither did the Bermuda Militia Artillery; the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps did get the pay rise.

- non-European regiments were also usually put into non-combatant roles especially if they were likely to fight Europeans. So while the West India Regiment saw active service in East Africa the other Caribbean regiments in France and the Middle East were attached to labour corps and undertook manual work such building and maintaining roads, railways and trenchs, dockyard work, and supplying artillery shells etc. Very dangerous work and usually under constant fire but they weren’t in actual combat.

- elsewhere black men were often in non-combative roles as mechanics, firemen, stokers, stewards, cooks, blacksmiths and clerks.

- there was high employment among black merchant seamen discharged in the UK because ships’ captains did not want to employ them and rather employ Chinese or white foreign sailors. The British government later put in place plans to repatriate black seamen.

Researching service personnel

Researching people from the Caribbean is challenging. Most government records do not record place of birth, nationality or ethnicity. Even if the records do record this information the catalogues and indexes do not always record this useful information. Other problems arise because reading handwritten documents can be very difficult and so mistakes are made. The country is not always written on the record – for example soldiers’ attestation papers ask for village or parish and county and so someone from Jamaica could quite correctly write Manchester, Middlesex and someone from the Bahamas may write Nassau, New Providence and from the Bermuda may write Sandys, Somerset. So, in addition to searching by country you may also need to search by island or parish or town.

There are four main types of records to look at when researching men and women who served in the armed forces and merchant navy:

- records of service and pension records (there are often separate collections for officers and other ranks) – these may be indexed by date and place of birth, and service number; the record may indicate ethnicity or complexion eg dark complexion or “man of colour”;

- medal rolls and index cards – name, rank, service number and unit (regiment or ship);

- operational records – unit (eg battalion or ship);

- casualty returns – name, unit and date of death (and may be burial site). The Commonwealth War Graves Commission database is the best place to start and will say where the person is commemorated.

Luckily for the Caribbean regiments there are also some lists of men (not indexed) and correspondence relating to some individuals in Colonial Office correspondence. As well as plenty of correspondence relating to policy.

Most of these records are available at The National Archives (UK) and searchable on their catalogue Discovery. Many can be downloaded from The National Archives or partner sites especially Ancestry and Findmypast; there will be a fee to download the images. Remember that the sources you’ll need to look at for Caribbean personnel are exactly the same as looking for people from Yorkshire or London.

I will describe some of the sources in later articles by for now the best place to start is by using The National Archives’ research guides.

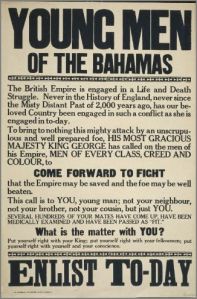

Image: Bahamas enlistment poster is from the Library of Congress and displayed on Wikimedia Commons (copied 5 May 2014)